James Bond in film

- For a topical guide to this subject, see Outline of James Bond.

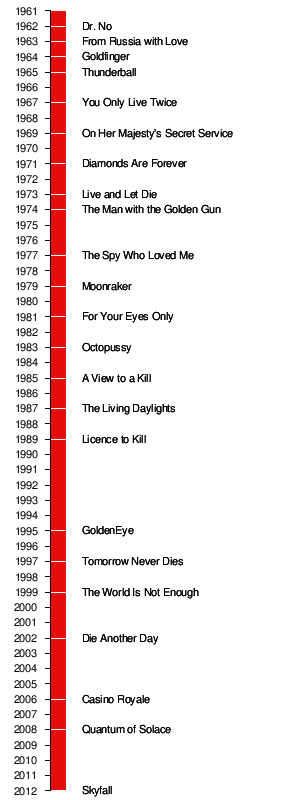

The James Bond film series is a British series of motion pictures based on the fictional character of MI6 agent James Bond (code designation "007"), who originally appeared in a series of books by Ian Fleming. Earlier films were based on Fleming's novels and short stories, followed later by films with original storylines. It is the longest continually-running film series in history, having been in ongoing production from 1962 to the present (with a six-year hiatus between 1989 and 1995).[1] In that time Eon Productions has produced 22 films, at an average of about one every two years, usually produced at Pinewood Studios. The series has grossed just over US$5 billion to date, making it the second-highest-grossing film series of all-time (behind Harry Potter).[2] Six actors have portrayed 007 in the Eon series, with the Connery films largely setting the style and mood of the series, and Roger Moore starring in the most films.

Albert R. Broccoli and Harry Saltzman co-produced the Eon films until 1975, when Broccoli became the sole producer. Since 1995, Broccoli's daughter Barbara and stepson Michael G. Wilson have co-produced them. Broccoli's (and until 1975, Saltzman's) family company, Danjaq, has held ownership of the series through Eon, and maintained co-ownership with United Artists since the mid-1970s. From the release of Dr. No (1962) up to For Your Eyes Only (1981) the films were distributed solely by UA. When Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer bought UA in 1981, MGM/UA Entertainment Co. was formed and distributed the films until 1995. MGM solely distributed three films from 1997 to 2002 after UA retired as a mainstream studio. From 2006 to present MGM and Columbia Pictures have co-distributed the franchise, following the 2005 acquisition of MGM by a consortium led by Columbia's parent company, Sony Pictures Entertainment. In November 2010, MGM filed for bankruptcy. Following MGM's emergence from bankruptcy, Columbia has been co-production partner of the series with Danjaq.

Independently of the Eon series, there have been three additional film or TV productions with the character of James Bond – a satirical film spoof based on Casino Royale (1967), a remake of Thunderball entitled Never Say Never Again starring Sean Connery (1983) and a pre-Eon 1954 American television adaptation of Casino Royale.

Development

First Bond film

Previous attempts to adapt the James Bond novels for screen resulted in a 1954 television episode of Climax!, based on the first novel, Casino Royale, and starring American actor Barry Nelson as "Jimmy Bond". Ian Fleming desired to go one step further and approached producer Sir Alexander Korda to make a film adaptation of either Live and Let Die or Moonraker. Although Korda was initially interested, he later withdrew.[3] On 1 October 1959, it was announced that Fleming would write an original film script featuring Bond for producer Kevin McClory. Jack Whittingham also worked on the script, culminating in a screenplay entitled James Bond, Secret Agent.[4] However, Alfred Hitchcock and Richard Burton turned down roles as director and star, respectively.[5] McClory was unable to secure the financing for the film, and the deal fell through. Fleming used the story for his novel Thunderball (1961).[6]

In 1959, producer Albert R. Broccoli expressed interest in adapting the Bond novels, but his colleague Irving Allen was unenthusiastic. In 1961, Broccoli, now partnered with Harry Saltzman, purchased the film rights to all the Bond novels (except Casino Royale) from Fleming.[7] However, numerous Hollywood film studios did not want to fund the films, finding it "too British" or "too blatantly sexual".[8] The producers wanted US$1 million to either adapt Thunderball or Dr. No, and reached a deal with United Artists in July 1961. The two producers set up Eon Productions and began production of Dr. No.[9]

| No. | Name | First film | Latest Eon film | No. of films | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | Release date | Age | Title | Release date | Age | |||

| 1. | Sean Connery | Dr. No | 5 October 1962 | 32 | Diamonds Are Forever | 14 December 1971 | 41 | 6 |

| 2. | George Lazenby | On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 12 December 1969 | 30 | On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 12 December 1969 | 30 | 1 |

| 3. | Roger Moore | Live and Let Die | 27 June 1973 | 45 | A View to a Kill | 22 May 1985 | 57 | 7 |

| 4. | Timothy Dalton | The Living Daylights | 30 June 1987 | 41 | Licence to Kill | 14 July 1989 | 43 | 2 |

| 5. | Pierce Brosnan | GoldenEye | 17 November 1995 | 42 | Die Another Day | 20 November 2002 | 49 | 4 |

| 6. | Daniel Craig | Casino Royale | 17 November 2006 | 38 | Skyfall | 26 October 2012 | 44 | 3 |

Sean Connery (1962–1967)

A contest was set up to 'find James Bond', and six finalists were chosen and screen-tested by Broccoli, Saltzman, and Fleming. The winner of the contest was a 28-year-old model named Peter Anthony, who, according to Broccoli, had a Gregory Peck quality, but proved unable to cope with the role.[10] The producers turned to Sean Connery, who ended up playing Bond for five consecutive films (and more subsequently). According to one story, Connery had been suggested by Polish director Ben Fisz, a friend of Saltzman. Saltzman viewed Connery in On the Fiddle (also called "Operation Snafu"), the actor's eleventh film. By other accounts, Broccoli first saw Connery in a screening of Darby O'Gill and the Little People (1959).[11]

Dr. No (1962)

Connery was not Broccoli and Fleming's first choice, but they accepted him after being rejected by Patrick McGoohan and rejecting Richard Johnson, James Mason, Rex Harrison, David Niven, Trevor Howard, and Broccoli's friend Cary Grant for various contractual impasses. Cary Grant was first choice but would only sign for one film instead of two; James Mason, the second choice, would only sign for two instead of three. Broccoli later said, "I wanted a ballsy guy...Put a bit of veneer over that tough Scottish hide and you've got Fleming's Bond instead of all the mincing poofs we had applying for the job". Already balding, Connery wore a toupee in all his Bond films. Connery stated that "the character is not really me, after all".[12] Ian Fleming, after seeing the preview screening of the first film, Dr. No, told his research assistant, "Dreadful. Simply dreadful."[13] Dr. No received mixed reviews, some quite hostile, and even received a rebuke by the Vatican.[13] Fleming eventually warmed up to Connery sufficiently to establish a Scottish ancestry for Bond in the late novels.

The role of Dr. No went to Joseph Wiseman, who had played a similar character in a The Twilight Zone episode "One More Pallbearer", after Noel Coward, Christopher Lee, and Max von Sydow were suggested.[14] (Both Lee and Sydow played Bond villains later, Sydow in the non-Eon Bond film Never Say Never Again.) With just two weeks to go before filming, the part of the first principal Bond girl, Honey Ryder, had yet to be cast. Director Young had seen a picture of Swiss-born actress Ursula Andress, then wife of John Derek, when visiting Darryl F. Zanuck over at Fox, and he borrowed the photo and showed it to the producers, who quickly approved the deal.[15]

From Russia with Love (1963)

On the next film, From Russia with Love, the producers doubled the budget, and shot locales in Europe, which had turned out to be the more profitable market for Dr. No.[16] Much of the team from the first film returned.[17] The film was the first to feature the pre-title sequence and the first to feature Desmond Llewelyn as Major Boothroyd, now called the Equipment Officer, who finally becomes Q in the third film. Llewelyn appears in a total of seventeen Bond films, the most for any actor playing the same role.[18] The final confrontation between Bond and assassin Donald Grant (Robert Shaw) takes place on the Orient Express and Bond owes his life to Major Boothroyd's deadly attaché case.[19] It is also the second and last film to feature the role of Sylvia Trench, who was supposed to continue through the series as Bond's somewhat regular bed partner between assignments.[20][21] The violence of the second film was decidedly pumped up from the previous film, with more than double the homicides.[22]

Adding to the appeal of mounting the picture, From Russia with Love was also cited by President John F. Kennedy as one of his ten favourite books,[23] although he was unlikely to have seen the film version, which was not released in the US until April 1964.[24] Some critics still resisted the Bond allure on the second Connery film, branding From Russia with Love "a movie made for kicks", but audiences loved it and some critics raved, such as Bosley Crowther who proclaimed "Don't Miss It!".[25] It is the first of the series to have virtually all the elements that appear throughout the series.[26]

Goldfinger (1964)

For the next film, Goldfinger, Guy Hamilton took over as director from Terence Young, putting more humour into Bond's character and more double entendres on the table.[27] For the important role of Pussy Galore, Honor Blackman was lured away from her role on the Avengers television series, which later offered up Diana Rigg as well.[28] For Auric Goldfinger, Theodore Bikel was considered but the role went to Gert Fröbe, a well-known actor in Europe, whose heavy accent required that his voice be dubbed.[29]

Goldfinger is the most noted Bond film by popular culture. The first appearance of the Aston Martin DB5 was in this film. The use of a menacing laser, newly invented just years before and not widely known to the public, was a cutting edge demonstration of real technology, and a set-up to perhaps one of the most memorable lines of the Bond films:

BOND: Do you expect me to talk?

GOLDFINGER: No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die![30]

The premiere in the UK created a near riot. In America, it became the fastest-grossing film ever to date. It was the first Bond film to win an Oscar (category: Best Effects, Sound Effects). Ian Fleming died before getting to see the film.[27]

Thunderball (1965)

By 1961, the Fleming Thunderball novel had become the biggest hit in the Bond novel series and was the project that re-attracted Cubby Broccoli to consider producing Bond projects in 1961 — most rights to which Harry Saltzman held, for he had acquired an option to the most of the Bond movie rights — with the notable exception of Thunderball, which was turned into a script in that year which became the centre of a long legal battle between screenwriters and Fleming.[31] Consequently Thunderball was not made by Eon until the legal obstacles had been cleared.[32] In a court case, McClory sued Fleming, because Fleming had used Thunderball's story and characters without permission. He won the film rights to Thunderball, so when Broccoli and Saltzman made Thunderball, it was a co-production with McClory. Part of the deal they made ensured McClory was unable to make Thunderball into a film for ten years.

Apart from Connery, the principal parts were hotly contested. For the lead Bond girl, Domino, a slew of top female actresses were considered including Raquel Welch, Julie Christie, and Faye Dunaway but the role went to former Miss France Claudine Auger.[33] Always with an eye toward European audiences, the producers gave the part of supervillain Emilio Largo to popular Italian actor Adolfo Celi.[34] Connery was eager to start but admitted in a pre-production interview that "My only grumble about the Bond films is that they don't tax one as an actor. All one needs is the constitution of a rugby player to get through 18 weeks of swimming, slugging, and necking… I'd like to see someone else tackle Bond."[34]

Connery would later state that Thunderball was his personal favourite performance as Bond (though in later statements, he claims that his favourite is From Russia with Love). Goldfinger was the fan-favourite from Dr. No to Diamonds Are Forever, though not Connery's favourite.[35] Thunderball was the most successful Bond film to date, based on total box office, earning $141.2 million[36] ($983 million in 2012 dollars[37]). It also inspired other spy films of the 1960s, including the "Harry Palmer" trilogy featuring Michael Caine, the "Derek Flint" series with James Coburn, and the "Matt Helm" series with Dean Martin.[38]

You Only Live Twice (1967)

In the fifth Bond film with Connery, You Only Live Twice, Bond comes face-to-face for the first time with arch-nemesis Blofeld (Donald Pleasence) Number One in SPECTRE, the world's most powerful criminal organisation. The title comes from a pseudo-haiku written by Fleming in the source novel, "You only live twice/Once when you're born/And once when you look death in the face."[39] The Bond films were hugely popular in Japan and when the crew arrived for shooting, they were treated exuberantly.[40] Connery, however, was somewhat resigned to the project, lacking the enthusiasm he sported for Thunderball.[41] Glimpses of Japanese culture were progressive (again a smart bow to Asian audiences by the producers) and the martial arts and ninja sequences novel for the time.[42]

You Only Live Twice is the very first James Bond film to jettison the plot premise of the Fleming source material, although the film retains the title, setting the plot entirely in Japan, the use of Blofeld as the main villain and a Bond girl named Kissy Suzuki—the backplot, plot and narrative were entirely screenwriter creations, and based in part on having already scouted locations such as Ninja castles and the volcanic mountains.[43] After You Only Live Twice, and despite the posters boasting that "Sean Connery is James Bond", Connery announced that it was his last film as Bond. The producers had no desire to give up the series and launched a search for a Bond actor for the next film.

George Lazenby (1969)

To replace Connery, Broccoli initially chose actor Timothy Dalton. However, Dalton declined, believing himself too young for the role.[44] The confirmed front runners were Englishman John Richardson, Dutchman Hans de Vries, American Robert Campbell, and Englishman Anthony Rogers.[45]

Broccoli and Hunt eventually chose Australian George Lazenby after seeing him in a Fry's Chocolate Cream advertisement.[46] Lazenby dressed the part by sporting several sartorial Bond elements such as a Rolex Submariner wristwatch and a Savile Row suit (ordered, but uncollected, by Connery), and going to Connery's barber at the Dorchester Hotel.[47] Broccoli noticed Lazenby as a Bond-type man based on his physique and character elements, and offered him an audition. The position was consolidated when Lazenby accidentally punched a professional wrestler, who was acting as stunt coordinator, in the face, impressing Broccoli with his ability to display aggression.[45] Lazenby was offered a contract for seven films; however, he was convinced by his agent Ronan O'Rahilly that the secret agent would be archaic in the liberated 1970s, and as a result he left the series after the release of On Her Majesty's Secret Service in 1969.[46]

Lazenby's reviews were quite mixed. Many felt that he was physically convincing in the action sequences, for which he did most of his own stunts, and that his portrayal was closer to the character in Fleming's novels, but that he looked foolish in his many loud costume changes, some featuring kilts, and delivered his lines poorly,[48] possibly because much of his dialogue was dubbed after the fact with the voice of a character whom he was impersonating through much of the film.[49] The film also featured the only breaking of the "fourth wall" in the Eon-produced Bond series, with Lazenby saying: "This never happened to the other fellow", a reference to Connery's Bond.[50]

In On Her Majesty's Secret Service, a conscious attempt was made to establish continuity with previous Bond films by showing scenes from those films during the title sequence. Furthermore, when Bond is packing up items in his office, several mementos of previous cases, such as the breathing device from Thunderball, are shown, while in the music score leitmotifs from the previous films are heard.

Sean Connery's return (1971)

After Lazenby's decision to only appear in one film, the producers decided to return to the formula of Goldfinger. Director Guy Hamilton returned, as well as the regular cast. John Gavin was offered the role of Bond and accepted, but the producers were simultaneously attempting to bring Sean Connery back to the role. To clinch the deal, Connery received a remarkable contract: a record $1.25 million salary, ($7 million in 2012 dollars[37]) plus 12.5 percent of the gross profits, and an additional $145,000 ($786,323 in 2012 dollars[37]) per week overtime if filming extended beyond 18 weeks. Connery admitted, "I was really bribed back into it... But it served my purpose... Playing James Bond again is still enjoyable."[51] The original idea was to bring back Auric Goldfinger for a sequel, but that was abandoned.[52] In Fleming's novels, Bond attempts to get revenge for the death of his wife in On Her Majesty's Secret Service in You Only Live Twice. But since the latter had been filmed prior to the former, Blofeld (played by English actor Charles Gray) is put into the story of Diamonds Are Forever to give Bond an opportunity to give Blofeld his comeuppance. This meant instead of Fleming's three stories about Blofeld (often published as the Blofeld trilogy), they had four. Connery returned to the role 12 years later in the non-Eon Never Say Never Again. For more see Non Eon-series column below.

Roger Moore (1973–1985)

In early 1972, the search for Connery's replacement began once again. Jeremy Brett, Michael Billington, and Julian Glover (who would later play Aristotle Kristatos in For Your Eyes Only) were considered for the next film in the series, Live and Let Die (1973), with the forty-five-year-old Roger Moore getting the nod.[53] Moore would become the longest-serving Bond, spending twelve years in the role and making seven films.[54][55]

Moore wanted to avoid imitating either Connery or his own performance as Simon Templar in The Saint and he opted to take a more light-hearted and comedic approach to the role.[56] In sharp contrast to Lazenby's introduction, the first two Moore films made a point to avoid common Bond film motifs: he smoked cigars rather than cigarettes and drank bourbon in place of a martini. It was during Moore's tenure in the role that Bond stopped smoking altogether. During the 1970s, the films became increasingly more comedic- mixing dark and even strange humour with violence. In regards to this new incarnation, one critic remarked "Roger Moore has none of the gravitas of Sean Connery… he does fit slickly into the director's presentation of Bond as a lethal comedian".[57]

Critics thought this Bond more of a charmer, more debonair, more calculating, and more casually lascivious in a somewhat detached but amused manner. He appears just as strong physically as Connery (at least in the early pictures), but not quite as graceful in action. Moore's adaptation applied more fantasy and humour than other Bonds. Despite some criticism, Moore's films proved successful enough to keep the franchise alive well into the 1980s with Moore playing the role into his fifties. The survival of the series can also be attributed to the addition of more contemporary themes (such as downplaying the Cold War era villains) and adding new characters to shore up the now-dated Fleming plots.[58]

Live and Let Die (1973), The Man with the Golden Gun (1974) and The Spy Who Loved Me (1977)

Despite mixed reviews, Live and Let Die was a box office success. From a budget estimated to be around $7 million, ($35 million in 2012 dollars[37]) the film grossed $126.4 million ($625 million in 2012 dollars[37]) worldwide.[59] The film holds the record for the most viewed broadcast film on television in the United Kingdom by attracting 23.5 million viewers when premiered on ITV on 20 January 1980.[60]

According to the British Film Institute, Moore's second Bond film, The Man with the Golden Gun, "is widely regarded as the most disappointing of the 1970s James Bond films"[61] and marked the end of Harry Saltzman's role as co-producer. Saltzman sold his 50% stake in Eon Productions's parent company, Danjaq, LLC, to United Artists (then owned by Transamerica Corp.) to alleviate his financial problems.[62]

Roger Moore's third film, The Spy Who Loved Me (1977), became a turning point for the series in two ways: it was the first film produced by Broccoli alone and also the first to include a completely original storyline, as Ian Fleming had given permission to use only the title of the novel.[63]

Moonraker (1979), For Your Eyes Only (1981), Octopussy (1983) and A View to a Kill (1985)

Moore's fourth film, Moonraker, was the last Bond film to use the title of a Fleming novel until 2006's Casino Royale. The next two films, For Your Eyes Only and Octopussy, used both of the titles of Bond short story anthologies and each incorporated material from multiple stories in those anthologies.

Moore showed interest in departing the series after 1981's For Your Eyes Only, and a string of younger actors, including James Brolin, Oliver Tobias, and Michael Billington, screen-tested for the part. However, Eon eventually persuaded him to return in 1983's Octopussy, due to the non-Eon Bond film, Never Say Never Again, being released in the same year.[64] Because he was rather old for the required action and the demands of the character (Moore was 55 at the time), stunt doubles were employed often (over a hundred stuntmen in total), and only the close-ups are surely Moore.[65] Moore would only regret his last film, A View to a Kill (1985), which was poorly received by critics.[66]

Timothy Dalton (1987–1989)

The Living Daylights (1987)

Timothy Dalton had been considered to replace Sean Connery in 1968, but he walked away from his screen test feeling, at the age of 22, that he was too young for the role.[67] Twelve years later, Dalton was approached again to possibly replace Roger Moore in For Your Eyes Only but the producers did not have a script and he feared being asked to do a Spy Who Loved Me/Moonraker type of film which "Weren't my idea of Bond films."[68] Dalton was the first actor to be offered The Living Daylights but initially had to turn it down as the original shooting date clashed with commitments on the film Brenda Starr. Pierce Brosnan was then cast, but when his cancelled television show Remington Steele was renewed in 1986, he was prevented from continuing.[66] Several actors were screen-tested, including Sam Neill and Lewis Collins, before Dalton was offered a revised production date which he was able to accommodate, and as soon as he wrapped shooting on Brenda Starr, Dalton found himself in the shoulder holster for The Living Daylights.[69]

Best known for his stage and television roles and trained in the British Shakespearean tradition, Dalton's Bond differs noticeably from his predecessors. The Guardian remarked, "Dalton hasn't the natural authority of Connery nor the facile charm of Moore, but Lazenby he is not."[70]

Licence to Kill (1989)

To save on production costs and taxes, Eon decided to shoot the next Bond film, Licence to Kill, in Mexico rather than at Pinewood Studios in the UK. The film's darker and more violent plot elicited calls for cuts by the British Board of Film Classification.[66] Licence to Kill is the first Bond film by Eon to not use the title of any Fleming novel or short story (although it uses material from the Fleming short story "The Hildebrand Rarity" and novel Live and Let Die). It and subsequent Bond films were novelised. Reviews for the film were mixed. With box office admissions close to that of The Man with the Golden Gun, the worst attended Bond film to date, some thought that replacing the basic style and elegance of a Bond film with realism was a mistake.[71]

In 1989, the same year of Dalton's second and last appearance, MGM/UA was sold to the Australian based broadcasting group Qintex, which wanted to merge the company with Pathé. Danjaq, the Swiss based parent company of Eon, sued MGM/UA because the Bond back catalogue was being licensed to Pathé, who intended to broadcast the series on television in several countries worldwide without the approval of Danjaq. These legal disputes engendered a six-year hiatus in the series. Nonetheless, Eon pre-production of another film began in May 1990, for release in late 1991. Generic promotional materials for "Bond 17" were unveiled at the Cannes Film Festival at around the same time. A detailed story draft, widely available online and spread over 17 pages, was written by Alfonso Ruggiero Jr. and Michael G. Wilson. The Walt Disney Imagineering division were also involved in the development of the high-tech robots prominent in that early treatment.[72]

Owing to the legal disputes, the production of Dalton's third film was postponed several times. In an interview in 1993, Timothy Dalton said that Michael France was writing the story for the film, which was due to begin production in January or February 1994.[73] It never began and, in April 1994, Dalton resigned from the role.[74]

Pierce Brosnan (1995–2002)

To replace Dalton, the producers cast Pierce Brosnan, whom they had met on the set of For Your Eyes Only when he came to visit his wife, Cassandra Harris (who had a small part as Countess Lisl von Schlaf), but had been prevented from taking over the role from Roger Moore in 1985 because of his contract for Remington Steele.[75][76] Shortly after Remington Steele was cancelled in 1987, Brosnan's wife was diagnosed with cancer and he cared for her until she died in 1991. In the next three years he worked only occasionally, and by 1994 he was ready to take on the Bond role. He stated his hopes for remaking Bond: "I would like to see what is beneath the surface of this man, what drives him on, what makes him a killer. I think we will peel back the onion skin, as it were".[71] He also relished the fact that Goldfinger was the first film he had ever seen and now he would get to play Bond, "Little did I think I would be playing the role someday."[77] Although little attention had been paid in the past to the Scottish background of Connery, Lazenby's Australian background, or the Welsh ancestry of Timothy Dalton, some British fans thought there was something odd about an Irishman playing Bond.[78]

GoldenEye (1995)

The Brosnan Bond smoked cigars and he favoured Italian-made suits. More importantly, Brosnan's GoldenEye was the first film of the series to be produced since the disintegration of the Soviet Union. This cast doubt over whether Bond was still relevant in the modern world, as many of the previous films pitted him against Soviet adversaries.[79] Gone was state-sponsored crime, now replaced by Russian mobs and gangsters. Another major change was casting Judi Dench as M, the head of MI6, reflecting that MI5 (the British Security Service) was then headed by a woman, Stella Rimington. Actress Samantha Bond was cast as Miss Moneypenny.[80]

Some of the film industry felt that it would be futile to make a comeback for the Bond series, and that it was best left as "an icon of the past".[81] However, when released, the film was viewed as a successful revivification that effectively adapted the series for the 1990s.[82] The film had the highest admissions since Connery's You Only Live Twice. Tom Shone commented, "Brosnan shares none of Connery's virtues but has also been careful to avoid Moore's vices. It doesn't give him much room for maneuver, but then maneuvering in tight corners is the one thing Brosnan is quite good at." Another critic stated, "The film is located precisely on the cusp between fantasy and near reality. For the first time in a Bond film there is something that could be called emotion", whilst another wrote that: "Bond is back with a bang."[80][83]

Tomorrow Never Dies (1997)

After the success of GoldenEye, there was pressure to recreate success in its follow-up, Tomorrow Never Dies, also at MGM. The studio had recently been sold to billionaire Kirk Kerkorian, who wanted the release to coincide with their public stock offering. Co-producer Michael G. Wilson said, "You realise that there's a huge audience and I guess you don't want to come out with a film that's going to somehow disappoint them." The rush to complete it meant the budget spiralled to around $110 million.[84] ($150 million in 2012 dollars[37]) Most of the locales were in Asia.

The World Is Not Enough (1999) and Die Another Day (2002)

Brosnan portrayed Bond in two more films, The World Is Not Enough (1999) and Die Another Day (2002), and a video game, Everything or Nothing, before it was announced by Eon that Brosnan was no longer required as the film series was about to be rebooted and the search for a new 007 (eventually Daniel Craig) was on. Though strong in their action scenes, production values, and acting, some critics found the final two Brosnan films to be too hyperkinetic with little time to savour the characters.[85]

Following the success of GoldenEye, Kevin McClory also attempted to remake Thunderball again as Warhead 2000. Liam Neeson and Timothy Dalton were considered for 007, while Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin were developing the film at Sony Pictures. MGM launched a $25 million lawsuit against Sony, and McClory claimed a portion of the $3 billion profits from the Bond series. Sony backed down after a prolonged lawsuit and McClory eventually ran out of legal avenues to go down. In exchange, MGM paid $10 million for the rights to Casino Royale, which had come into Sony's possession after its acquisition of the companies behind Climax! years before.[5]

Daniel Craig (2006–present)

Pierce Brosnan had originally signed a deal for three films, with an option for a fourth, when he was cast in the role of James Bond. This was fulfilled with the production of Die Another Day in 2002. However, at this stage Brosnan was approaching his 50th birthday, and speculation began that the producers were seeking to replace him with a younger actor.[86] Brosnan kept in mind that both aficionados and critics were unhappy with Roger Moore playing the role until he was 58, but he was receiving popular support from both critics and the franchise fanbase for a fifth instalment and for this reason, he remained enthusiastic about reprising his role.[87] Throughout 2004, it was rumoured that negotiations had broken down between Brosnan and the producers to make way for a new and younger actor,[88] although this was denied by MGM and Eon Productions. In July 2004, Brosnan announced that he was quitting the role, stating "Bond is another lifetime, behind me"; this is thought by some to be a failed negotiating ploy.[89]

Casting involved a widespread search for a new actor to portray James Bond and throughout 2004 and 2005, a number of potential new actors were speculated upon by the media, ranging from established Hollywood actors, such as Eric Bana, Hugh Jackman, James Purefoy, Dougray Scott, Henry Cavill, Goran Višnjić, Julian McMahon, Gerard Butler, and Clive Owen, to many unknown actors from a number of different countries, including Sam Worthington, Alex O'Loughlin, and Rupert Friend.[90] At one point producer Michael G. Wilson claimed there was a list of over 200 names being considered.[91] English actor Colin Salmon, who had played the role of MI6 operative Charles Robinson in earlier Bond films alongside Pierce Brosnan, was also considered for the role and raised speculation that he would become the first black Bond.[92] According to Martin Campbell, however, Cavill was the only actor in serious contention for the role, but being only 22 years old at the time, he was considered too young.[93]

In May 2005, Daniel Craig announced that Sony and MGM and producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli had assured him that he would get the role of Bond, but Eon Productions at that point had not yet approached him.[94] Later, Craig stated that the producers had indeed offered him the role, but he had declined until a script was available for him to read.[95]

Casino Royale (2006)

Bolstered by the success of Universal Pictures' rival Jason Bourne franchise (as well as Warner Bros.’ reboot of the Batman franchise with Batman Begins), the decision was made at MGM and Eon to "bring Bond back to his roots" by eliminating the gadgets and fantasy elements that had begun to define the series, and introducing a tougher, darker, and more realistic Bond that was more in line with the Bond of Ian Fleming's original novels than with any of his previous screen incarnations. Thus, the 21st Bond film, Casino Royale, in addition to being the first film adaptation of a Fleming novel since 1969's On Her Majesty's Secret Service, was to be a reboot of the franchise, establishing a new timeline and narrative framework not meant to precede any previous film.[96] This not only freed the Bond franchise from more than forty years of continuity, but allowed the film to show a less experienced and more vulnerable Bond.[97] As with the previous introductions of new Bonds, the film provided the opportunity to remove production excesses and to get back to basics.[98]

By August 2005, speculation was high that the then 37-year-old Daniel Craig was being seriously considered, although full casting for the role was not actually completed until September. On 14 October 2005, Eon Productions and Sony Pictures Entertainment confirmed to the public at a press conference in London that Daniel Craig, who would soon become one of the stars of Steven Spielberg's Munich, would be the sixth actor to portray James Bond.[99] Significant controversy followed the decision, as it was doubted if the producers had made the right choice. Throughout the entire production period Internet campaigns such as danielcraigisnotbond.com expressed their dissatisfaction and threatened to boycott the film in protest.[100] Craig, unlike previous actors, was not considered by the protesters to fit the tall, dark, handsome and charismatic image of Bond to which viewers had been accustomed.[101] The Daily Mirror ran a front page news story critical of Craig, with the headline, The Name's Bland — James Bland.[102] However, reviews for Casino Royale were favourable and the film became the highest grossing Bond film since Moonraker. Roger Ebert commented, "Daniel Craig makes a superb Bond: leaner, more taciturn, less sex-obsessed, able to be hurt in body and soul, not giving a damn if his martini is shaken or stirred."[103]

Quantum of Solace (2008)

As production of Casino Royale reached its conclusion, producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli announced that pre-production work had already begun on the 22nd Bond film. After several months of speculation as to the release date, Wilson and Broccoli announced on 20 July 2006 that the follow-up film, Quantum of Solace,[104] would be released on 2 May 2008 and that Craig had been signed to play Bond, with an option for a third film.[105] Quantum of Solace was eventually released on 31 October 2008 in the UK and 14 November 2008 in North America, changed from its original release date of 7 November 2008 after Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was pushed back to summer 2009. Upon its opening in the UK, it grossed £4.9 million, breaking the record for the largest Friday opening (31 October 2008) in the UK.[106] The film then broke the UK opening weekend record, taking £15.5 million in its first weekend, surpassing the previous record of £14.9 million held by Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire.[107][108] The film grossed $27 million on its opening day in 3,451 cinemas in Canada and the United States. It was the #1 film for the weekend, with $67.5 million and $19,568 average per cinema.[109] It was the highest-grossing opening weekend Bond film in the US and Canada,[110] and tied with The Incredibles for the biggest November opening outside of the Harry Potter series.[111]

Columbia Pictures co-financed and distributed Craig's first two films because they bought MGM in 2005. However, MGM chose to cease the distribution deal with Columbia following the success of Casino Royale (for which Columbia provided 75% of the budget). In the agreement, Columbia chose to finance one more Bond film, Quantum of Solace.[112] However, in April 2011, a deal was finalized allowing Columbia/Sony to continue to be involved with the James Bond film series, picking up where they left off with Bond 23 and Bond 24.[113] Despite the renewed 007 partnership, 20th Century Fox will continue to handle home video rights to the film series on behalf of MGM as Fox's output distribution deal was also renewed in April 2011.

Skyfall (2012)

Skyfall, then known by the working title Bond 23, was suspended throughout 2010 because of MGM's financial troubles; however, following MGM's exit from bankruptcy on 21 December 2010, Bond 23 resumed pre-production and in January 2011 was officially given a release date of 9 November 2012 by MGM and the Broccoli family, with production scheduled to start in late 2011. Since then, MGM and Sony Pictures announced that the UK and Ireland release date would be brought forward to 26 October 2012, two weeks prior to the USA release date, which will remain November 9.[114] The film will be part of yearlong celebrations of the 50th anniversary of Dr. No and the Bond franchise. Following speculation that the film would be titled "Skyfall" after a series of domain names were discovered to have been registered on behalf of Sony Pictures,[115] the title was officially confirmed at a press conference on 3 November 2011, fifty years to the day since Sean Connery was annouced to be the first James Bond. The film will be directed by Sam Mendes.

Peter Morgan was originally commissioned to write a script, but left the project when MGM filed for bankruptcy and production of the film stalled. The final script was written by Bond screenwriting regulars Neal Purvis and Robert Wade, as well as John Logan.[116][117][118] Roger Deakins will be the film's cinematographer, having previously worked with Mendes on Jarhead and Revolutionary Road.[119]

Judi Dench was confirmed as reprising her role as M and revealed that she was needed by the production team as early as November 2011.[120] In January 2011, Deadline.com reported that Eon Productions offered Javier Bardem a starring role.[121] In an October 2011 interview with Christiane Amanpour for ABC's Nightline, Bardem confirmed his role in the film.[122] British actors Ralph Fiennes[123] and Albert Finney[124] were connected to roles, and confirmed to be a part of the cast at the November press event. The producers met with Naomie Harris; while it was initially reported that she would be cast as Miss Moneypenny, Harris revealed that she will play a field agent named Eve.[125] Ben Whishaw has been cast as Q.[126]

Sam Mendes and Barbara Broccoli travelled to South Africa for location scouting in April, 2011.[127] With the film moving into pre-production in August, reports emerged that shooting would take place in India,[128] with scenes to be shot in the Sarojini Nagar district of New Delhi[129] and on railway lines between Goa and Ahmedabad,[130] but complications emerged when the Indian authorities requested changes be made to planned scenes,[131] and plans to shoot in India were abandoned.[132] Further reports emerged stating that filming of the film's opening scenes would take place in Istanbul's Sultanahmet Square[133] and Duntrune Castle in Argyll, Scotland for the finale.[134] Mendes confirmed that China would be featured in the film, with shooting scheduled to take place in Shanghai.[135]

Actors of recurring characters

Note that 'M' and 'Q' are ranks, so they are technically not single characters being played by several actors, except for the transition from Dr. No's Peter Burton to Desmond Llewellyn playing Q. These are both Major Boothroyd.

Non-Eon films

Prior to Eon's start in 1961, Casino Royale was adapted as a one-hour television episode of CBS's series Climax!. The nationalities of James Bond and Felix Leiter were reversed making Bond American and Leiter British. Bond was nicknamed "Card sense Jimmy Bond".[136] After Eon's formation, only two James Bond films were produced without the company's consent, due to the production rights of two Ian Fleming novels being lost. In 1955, Ian Fleming sold the film rights of Casino Royale to producers Michael Garrison and Gregory Ratoff. These were later sold to producer Charles K. Feldman. Feldman initially went to Broccoli and Saltzman with a proposition to produce the film; however, due to their negative experiences with Kevin McClory on Thunderball they declined. Feldman decided to start his own production and approached Connery who offered to do the film for $1 million dollars, which Feldman rejected. Since his previous film, the madcap comedy What's New, Pussycat?, had been a success, Feldman decided to make a satirical Bond film in similar vein. Problems ensued, however, when the star, Peter Sellers, walked off the project with scenes uncompleted, and script re-writes and directorial changes (the film ended up with five) caused the budget to escalate far beyond that of any Bond picture hitherto. The Casino Royale spoof was released in 1967. The plot involves multiple impersonators of James Bond as the real one played by David Niven is now elderly. Thus Peter Sellers' character is engaged in the Casino showdown with LeChiffre as done by James Bond in Fleming's novel. Woody Allen in addition to playing an inept nephew of James Bond, called Jimmy Bond,[137] also did uncredited script work on the film,[138] in which his persona resembles that of his character in his earlier film What's New Pussycat.[139]

When plans for a James Bond film were scrapped in the late 1950s, a story treatment entitled Thunderball, written by Ian Fleming, Kevin McClory and Jack Whittingham, was adapted as Fleming's ninth Bond novel. Initially the book was only credited to Fleming. McClory filed a lawsuit that would eventually award him the film rights to the title in 1963. Afterwards, he made a deal with Eon Productions to produce a film adaptation starring Sean Connery in 1965. The deal stipulated that McClory could not produce another adaptation until a set period of time had elapsed, and he did so in 1983 with Never Say Never Again, which featured Sean Connery for a seventh time as 007. The film was a worldwide box-office success, but since it was not made by Broccoli's production company, Eon Productions, it is not considered a part of the Eon film series. A second attempt by McClory to remake Thunderball in the 1990s with Sony Pictures was halted by a legal dispute resulting in the studio abandoning its aspirations for a rival James Bond series.[5]

MGM later acquired the rights for both films. Never Say Never Again (originally released by Warner Bros.) was bought from Taliafilm in 1997,[140] and Casino Royale was acquired from Sony, along with the adaptation rights of the novel, in exchange for $10 million and the filming rights of Spider-Man.[141]

Bond spinoffs, unauthorised films and spoofs

In 1991, Fred Wolf films produced a cartoon series producing 65 episodes of James Bond, Jr.. The character is actually the nephew of James Bond, and the cartoon had episodes of villains from the film series, including Dr. No and Jaws.

The 1983 TV film The Return of the Man from U.N.C.L.E.: The Fifteen Years Later Affair brought back the characters from the Bond-inspired 1960s television series The Man from U.N.C.L.E.. In one scene former Bond actor George Lazenby has a short cameo as a Bond-like character driving an Aston Martin with the license plate "JB007".

Unauthorized appearances of James Bond include a few full-length spoofs, including an "Agent 007" character in the Spanish spoof film The Amazing Doctor G (1965) with a villain named Goldginger (sic), and the Norwegian spy spoof Goldenrock (1999).

Foreign films with James Bond include the Hong Kong Bruce Lee martial arts thriller Deadly Hands of Kung Fu (1977) (made after Bruce Lee's death), and the Indian film James Bond 777 (1971). The Italian film OK Connery (1967) stars Sean Connery's younger brother, Neil Connery, in the role of the secret agent and additionally features stars from the Bond film series.

Bond is a character in several comedy shorts (some as short as 3 minutes) including Bondage (2001) Never a Day Younger (2006) and Shaken Not Stirred (2006), Casino Royale With Cheese (2007), Gold Is Not Enough (2009), and 99 Cent Bond (2009).

The late-night British comedy TV series Mainly Millicent had a few James Bond spoofs in which Roger Moore played Bond in 1964, 7 years before his being cast in the Eon series.

Reception

The films have been awarded two Academy Awards: for Sound Effects (now Sound Editing) in Goldfinger (1964) and for Visual Effects in Thunderball (1965). In 1982, Albert R. Broccoli received the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award.[142] Additionally, several of the songs, including Paul McCartney's "Live and Let Die", Carly Simon's "Nobody Does It Better", and Sheena Easton's "For Your Eyes Only", have been nominated for Academy Awards for Original Song.

The spy novelist John le Carré was severely critical of the character of James Bond, regarding Bond as potential traitor material. le Carré created his spy George Smiley as the antithesis of Bond. Smiley is shy, cerebral, and shabbily dressed; his spy work is mostly mundane and plodding; he gets caught up in morally ambiguous situations, and his wife is cheating on him. Both le Carré's novel The Honourable Schoolboy and Fleming's Japan-based book You Only Live Twice have a character based on real journalist Richard Hughes.

Film critic Mick LaSalle notes many believe the older Bond films were superior to the later films, which he disagrees with, arguing many of the older films "[benefit] mainly from a certain James Bond atmosphere and from a built-up sense of audience expectation". He also feels every James Bond actor was "first rate". Upon re-watching all the films, LaSalle was surprised by how rough Connery's Bond was, and felt it was Moore "who [brought] radiant narcissism and [an] effete quality" to the character. He added "Brosnan was superb [for] combining Moore's self-satisfaction with Dalton's sensitivity," while Craig became his favourite Bond by his second film for "reconceiv[ing] the role for himself as a young tough guy with a lot of pain going on inside".[143] In 2007, IGN chose the James Bond series as the second best film franchise of all time, behind Star Wars.[144] Sean Connery's version of James Bond was ranked #11 on Empire's 100 Greatest Movie Characters.

Review aggregate results

| Eon Productions films | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion picture | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic | BFCA | |

| Overall | Top Critics | |||

| Dr. No | 98% (43 reviews)[145] | 100% (6 reviews)[146] | ||

| From Russia with Love | 96% (46 reviews)[147] | 100% (10 reviews)[148] | ||

| Goldfinger | 96% (49 reviews)[149] | 89% (9 reviews)[150] | ||

| Thunderball | 88% (34 reviews)[151] | 100% (6 reviews)[152] | ||

| You Only Live Twice | 70% (33 reviews)[153] | 38% (8 reviews)[154] | ||

| On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 82% (38 reviews)[155] | 71% (7 reviews)[156] | ||

| Diamonds Are Forever | 67% (36 reviews)[157] | 75% (8 reviews)[158] | ||

| Live and Let Die | 64% (36 reviews)[159] | 63% (8 reviews)[160] | ||

| The Man with the Golden Gun | 52% (33 reviews)[161] | 14% (7 reviews)[162] | ||

| The Spy Who Loved Me | 79% (38 reviews)[163] | 50% (6 reviews)[164] | ||

| Moonraker | 64% (36 reviews)[165] | 63% (8 reviews)[166] | ||

| For Your Eyes Only | 69% (36 reviews)[167] | 43% (7 reviews)[168] | ||

| Octopussy | 47% (32 reviews)[169] | 57% (7 reviews)[170] | ||

| A View to a Kill | 39% (41 reviews)[171] | 14% (7 reviews)[172] | ||

| The Living Daylights | 73% (33 reviews)[173] | 71% (35 reviews)[174] | ||

| Licence to Kill | 71% (35 reviews)[175] | 57% (7 reviews)[176] | ||

| GoldenEye | 80% (41 reviews)[177] | 70% (10 reviews)[178] | 65 (18 reviews)[179] | |

| Tomorrow Never Dies | 55% (56 reviews)[180] | 60% (10 reviews)[181] | 56 (21 reviews)[182] | |

| The World Is Not Enough | 51% (113 reviews)[183] | 44% (9 reviews)[184] | 59 (33 reviews)[185] | |

| Die Another Day | 59% (192 reviews)[186] | 57% (14 reviews)[187] | 56 (37 reviews)[188] | 74 [189] |

| Casino Royale (2006) | 94% (216 reviews)[190] | 88% (17 reviews)[191] | 81 (38 reviews)[192] | 88 (Critics Choice) [193] |

| Quantum of Solace | 64% (243 reviews)[194] | 58% (19 reviews)[195] | 58 (38 reviews)[196] | 81 (Critic's Choice) [197] |

| Non-Eon films | ||||

| Motion picture | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic | BFCA | |

| Overall | Top Critics | |||

| Casino Royale (1967) | 29% (31 reviews)[198] | 29% (7 reviews)[199] | ||

| Never Say Never Again | 65% (34 reviews)[200] | 71% (7 reviews)[201] | ||

Box office results

| Franchise count | Title | Year | Actor | Director | Total box office * | Budget * | Inflation adjusted total box office *† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. No | 1962 | Sean Connery | Terence Young | $59,600,000 | $1,200,000 | $425,488,741 |

| 2 | From Russia with Love | 1963 | $78,900,000 | $2,500,000 | $555,909,803 | ||

| 3 | Goldfinger | 1964 | Guy Hamilton | $124,900,000 | $3,500,000 | $868,659,354 | |

| 4 | Thunderball | 1965 | Terence Young | $141,200,000 | $11,000,000 | $966,435,555 | |

| 5 | You Only Live Twice | 1967 | Lewis Gilbert | $111,600,000 | $9,500,000 | $720,388,023 | |

| 6 | On Her Majesty's Secret Service | 1969 | George Lazenby | Peter R. Hunt | $87,400,000 | $7,000,000 | $513,445,231 |

| 7 | Diamonds Are Forever | 1971 | Sean Connery | Guy Hamilton | $116,000,000 | $7,200,000 | $617,520,987 |

| 8 | Live and Let Die | 1973 | Roger Moore | $161,800,000 | $12,000,000 | $785,677,477 | |

| 9 | The Man with the Golden Gun | 1974 | $97,600,000 | $13,000,000 | $426,826,774 | ||

| 10 | The Spy Who Loved Me | 1977 | Lewis Gilbert | $187,300,000 | $28,000,000 | $666,367,656 | |

| 11 | Moonraker | 1979 | $210,300,000 | $34,000,000 | $624,527,272 | ||

| 12 | For Your Eyes Only | 1981 | John Glen | $202,800,000 | $28,000,000 | $481,005,579 | |

| 13 | Octopussy | 1983 | $187,500,000 | $27,500,000 | $405,873,493 | ||

| 14 | A View to a Kill | 1985 | $157,800,000 | $30,000,000 | $316,186,616 | ||

| 15 | The Living Daylights | 1987 | Timothy Dalton | $191,200,000 | $40,000,000 | $362,876,056 | |

| 16 | Licence to Kill | 1989 | $156,200,000 | $32,000,000 | $271,586,451 | ||

| 17 | GoldenEye | 1995 | Pierce Brosnan | Martin Campbell | $353,400,000 | $60,000,000 | $499,954,330 |

| 18 | Tomorrow Never Dies | 1997 | Roger Spottiswoode | $346,600,000 | $110,000,000 | $465,588,535 | |

| 19 | The World Is Not Enough | 1999 | Michael Apted | $390,000,000 | $135,000,000 | $504,705,882 | |

| 20 | Die Another Day | 2002 | Lee Tamahori | $456,000,000 | $142,000,000 | $546,490,272 | |

| 21 | Casino Royale | 2006 | Daniel Craig | Martin Campbell | $599,200,000 | $150,000,000 | $640,803,677 |

| 22 | Quantum of Solace | 2008 | Marc Forster | $586,090,727 | $230,000,000 | $586,090,727 | |

| 23 | Skyfall | 2012 | Sam Mendes | TBA | |||

| Totals | Films 1–23 | $4,809,157,447 | $1,123,000,000 | $11,686,214,000 |

* All figures are in US Dollars[202]

† Figures are inflated to 2008 dollars as of 24 March 2008 figures based on the Consumer Price Index.

Influence

The success of the James Bond series in the 1960s led to various spy TV series, both comical as in Get Smart or straight thriller series such as I Spy, and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., the last having enjoyed contributions by Fleming towards its creation. There was also an increase in the market for spy films such as the Harry Palmer films which starred Michael Caine.

Bond has also received many homages and parodies in popular media. Especially notable is the Austin Powers series by writer, producer and comedian Mike Myers as many characters in it are parodies of specific characters in the Bond films. Other notable parodies include Spy Hard (1996), Johnny English (2003), Bons baisers de Hong Kong, OK Connery, Undercover Brother (2002), the films Our Man Flint and In Like Flint starring James Coburn as Derek Flint, and the "Matt Helm" films starring Dean Martin.[203]

Eon productions or MGM have been known to file suit in one form or another if they think the copying of Bond is too close. A suit against the producers of the third Austin Powers film ended in a settlement in which the distributors of the latter agreed to show a trailer of the forthcoming Bond film in cinemas prior to their film.[204] A season 4 episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine entitled Our Man Bashir featured a virtual-reality game on the holodeck with multiple James Bond references in sufficient amount to raise the ire of MGM.[205]

George Lucas has said on various occasions that Sean Connery's portrayal of Bond was one of the primary inspirations for the Indiana Jones character, a reason Connery was chosen for the role of Indiana's father in the third film, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.[206][207]

DVD releases

GoldenEye and Tomorrow Never Dies were the first in the series to be released on DVD in 1998. Following The World Is Not Enough on 22 May 2000, the series proper was issued chronologically in single disc "special editions" over the next ten months until 26 March 2001.[208] At first, three boxed sets with the films up to Tomorrow Never Dies were released.[209] In 2003, following the DVD release of Die Another Day, all films were available in both a twenty-film case or three box sets.[210]

In July 2006, the entire series was re-released in "Ultimate Edition" two-disc sets that featured frame-by-frame digitally restored picture by Lowry Digital and remixed DTS sound.[211] Throughout 2007 these editions were released in four non-chronological boxed sets, each containing five titles. They were eventually combined in an "ultimate collector's set" that included the two-disc widescreen edition of Casino Royale. They also saw single-disc releases which were essentially "disc one" of the "Ultimate Editions".

On 20 October 2008, to tie in with the cinema debut of Quantum of Solace, six non-consecutive titles in the series were released on Blu-ray Disc,[212] along with a special edition re-release of Casino Royale.[213] On March 29, 2009, both a third pack with three other films,[214] and Quantum of Solace were released.[215] Never Say Never Again was also released in this format.[216]

Video game adaptations

James Bond has starred in many video games, with a few being direct adaptations of the films. Between 1985 and 1990, Mindscape made text adventure versions of Goldfinger and A View to a Kill, and Domark produced side scrolling shooter games based on Licence to Kill, The Spy Who Loved Me, The Living Daylights, Live and Let Die and A View to a Kill.

The popularity of the James Bond video game did not really take off, however, until 1997's GoldenEye 007, a Nintendo 64 first-person shooter developed by Rare based on GoldenEye, along with additional and extended missions.[217] It received the BAFTA Interactive Entertainment "Games Award" and is widely considered one of the best games ever.[218][219] Electronic Arts released two tie-in games, the third-person shooter Tomorrow Never Dies (1997, PlayStation) and the first-person shooter The World Is Not Enough (2000, PlayStation, N64 and Game Boy Color) before starting original games, such as Agent Under Fire (2001, PlayStation 2, Xbox and GameCube) and Nightfire (2002, PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube, Windows, Macintosh and Game Boy Advance), which were the most similar games to the style of GoldenEye, and GoldenEye: Rogue Agent (2004, PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube and Nintendo DS), which bears no relation to the film GoldenEye, nor the game of the same title. EA also released Everything or Nothing (2004, PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube and Game Boy Advance), a third-person shooter starring Pierce Brosnan in his fifth and final appearance as 007. The success of this game led to a follow-up based on From Russia with Love (2005, PlayStation 2, Xbox, GameCube and PlayStation Portable), which even included Sean Connery's likeness and voice acting.

After EA, Activision got the rights to games based on the Bond franchise, and has since released two titles based on films: 2008's Quantum of Solace, based on both the eponymous film and Casino Royale, and 2010's GoldenEye 007, a remake of the critically acclaimed 1997 game, which updates the plot of GoldenEye to a contemporary setting and features the voice and likeness of current Bond actor Daniel Craig.

Broadcast television airings

In the UK, Bond films became a staple of ITV's public holiday television. They have also been frequently shown as full runs in chronological order, especially prior to the premiere of the latest offering. The 1980 premiere broadcast of Live and Let Die holds the record for the most watched film of all time on British television, with an audience of 23.50 million.[220]

In 1972, ABC bought the broadcasting rights to the James Bond franchise;[221][222][223] this continued until 1990, when The Living Daylights was the final film aired prior to Turner Broadcasting[224] buying the TV airing rights (with TBS airing them under the 15 Days of 007[225] umbrella). The Bond films have also aired on several cable channels not owned by Turner. ABC broadcast the films again as a promotional tie-in when Die Another Day was in cinemas in 2002, dubbed as The Bond Picture Show on Saturday nights.

See also

References

- ^ "James Bond film suspended". London: The Telegraph. 20 April 2010. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/7608854/James-Bond-film-suspended.html. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- ^ "Harry Potter becomes highest-grossing film franchise". London: The Guardian. 11 September 2007. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2007/sep/11/jkjoannekathleenrowling. Retrieved 28 September 2011.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 255.

- ^ Caplen 2010, p. 73.

- ^ a b c "The Lost Bond". Total Film. 27 February 2008. http://www.totalfilm.com/features/the-lost-bond. Retrieved 19 March 2008.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Cork & Scivally 2006, p. 31.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 8-9.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 16.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 33-35.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 56.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 67.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 66.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Dodds, Klaus (2005). "Screening Geopolitics: James Bond and the Early Cold War films (1962-1967)". Geopolitics 10 (2): 266–289. doi:10.1080/14650040590946584.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 36.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 62-64.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 41.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 34.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 48.

- ^ Chapman 2009, p. 184.

- ^ Poliakoff, Keith (2000). "License to Copyright - The Ongoing Dispute Over the Ownership of James Bond". Cardozo Arts & Entertainment Law Journal (Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law) 18: 387–436. http://www.cardozoaelj.net/issues/00/Poliakoff.pdf. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 45.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 46.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 103.

- ^ "Thunderball". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. http://the-numbers.com/movies/series/JamesBond.php. http://www.the-numbers.com/movies/1965/0THBA.php. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved 7 December 2010.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 74.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 82.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 140.

- ^ The Bond Documentaries on DVD

- ^ Inside The Living Daylights (DVD). The Living Daylights, Ultimate Edition Disk 2: MGM Home Entertainment. 2000.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 82.

- ^ a b Inside On Her Majesty's Secret Service (DVD). OHMSS Ultimate Edition DVD: MGM Home Entertainment Inc. 2000.

- ^ "De 'vergeten' 007". Andere Tijden. VPRO. Nederland 2, Amsterdam. 19 November 2002.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 159.

- ^ "On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969)". Screenonline. British Film Institute. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/550393/credits.html. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 173.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 186.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 128.

- ^ (NTSC, Widescreen, Closed-captioned) Inside Live and Let Die: Live and Let Die Ultimate Edition, Disc 2 (DVD). MGM/UA Home Video. 2000. ASIN: B000LY209E.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 117.

- ^ "Live and Let Die". The Numbers. Nash Information Service. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/movies/lald.php3. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

- ^ "TV's jewels fail to shine in list of all-time winners". Electronic Telegraph. 7 February 1998. http://www.corrie.net/chat/ratucs/press/top100.html. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Brooke, Michael. "The Man with the Golden Gun (1974)". BFI Screenonline. The British Film Institute. http://www.screenonline.org.uk/film/id/505543/. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 141-142.

- ^ (2000). Inside The Spy Who Loved Me [DVD]. MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ (2000). Inside Octopussy [DVD]. MGM Home Entertainment. Retrieved on 4 August 2007.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 169.

- ^ "Derby - Around Derby - Famous Derby - Timothy Dalton biography". BBC. http://www.bbc.co.uk/derby/features/famous_derby/timothy_dalton.shtml. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ Copyright 1998-2007. "James Bond 007 :: MI6 - The Home Of James Bond". MI6. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/dalton_bond_era.php3. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- ^ Inside The Living Daylights (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 178.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 192.

- ^ "GoldenEye - The Road To Production". mi6-hq.com. 23 June 2003. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/ge_roadtoproduction.php3. Retrieved 4 January 2007.

- ^ "Interview with Dalton". Daily Mail. 6 August 1993.

- ^ Michael G. Wilson, Martin Campbell, Pierce Brosnan, Judi Dench, Desmond Llewelyn (1999). The Making of 'GoldenEye': A Video Journal (DVD). MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Fox, Maggie (8 June 1994). "Pierce Brosnan Is New James Bond". Reuters. http://www.klast.net/bond/ge_news2.html. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Last, Kimberly (1995). "Pierce Brosnan's Long and Winding Road To Bond". GoldenEye (magazine). http://www.klast.net/bond/pb_road.html. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 196.

- ^ Stein, Ruthe (5 November 1995). "Pierce Brosnan Spies A 'Golden' Opportunity / Actor finally gets his shot at playing James Bond". Sfgate.com. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/1995/11/05/PK70865.DTL&type=printable. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Comentale, Edward P.; Stephen Watt, Skip Willman (2005). Ian Fleming and James Bond: The Cultural Politics of 007. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253345233. OCLC 224330102.

- ^ a b Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Pfeiffer & Worrall 1998, p. 169.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (16 November 1995). "GoldenEye". Variety. http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117904690.html?categoryid=31&cs=1. Retrieved 18 November 2006.

- ^ Smith & Lavington 2002, p. 252.

- ^ Ashton, Richard (1997). "Tomorrow Never Dies". hmss.com. http://www.hmss.com/films/mgw/mgw97.html. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ Lipp 2006, p. 430.

- ^ "Is Brosnan too old to be 007?". London: Daily Mail. 9 February 2004. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-207653/Is-Brosnan-old-007.html. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ^ "Brosnan uncertain over more Bond". BBC. 4 April 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3592361.stm. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ "Is Brosnan too old to be 007?". London: Daily Mail. 9 February 2004. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/pages/live/articles/showbiz/showbiznews.html?in_article_id=207653&in_page_id=1773. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ Rich, Joshua (27 July 2004). "Bond No More". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,673018,00.html. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- ^ "Dallas & Casino Royale Casting Rumors". Variety. MovieWeb, Inc. 28 September 2005. http://www.movieweb.com/news/NEgidojlcR2Njh. Retrieved 21 March 2007.

- ^ "Daniel Craig takes on 007 mantle". BBC. 14 November 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4337224.stm. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ "Bets off as actor backed for Bond". BBC. 4 December 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4065229.stm. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- ^ Chavez, Kellvin. "Exclusive interview with Martin Campbell on Zorro and Bond". Latino Review. http://www.latinoreview.com/news/campbell-talks-zorro-2-casino-royale-109. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ^ "Craig, Vaughn on Bond". IGN Entertainment, Inc.. 3 May 2005. http://movies.ign.com/articles/609/609721p1.html. Retrieved 10 August 2006.

- ^ Jeffries, Stuart (17 November 2006). "Seven's Deadly Sins". London: Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2006/nov/17/jamesbond. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ "IGN: Interview: Campbell on Casino Royale". IGN.com. IGN Entertainment, Inc. 19 October 2005. http://movies.ign.com/articles/659/659741p1.html. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ "New James Bond Proves Worthy of Double-0 Status". SPACE.com. 21 October 2006. http://www.space.com/entertainment/061116_bond_review.html. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ^ Blair, Iain (October 2006). "Martin Campbell: Casino Royale; James Bond gets back to basics in this new installment". Post Magazine. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HNN/is_10_21/ai_n27098544/. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ^ "Daniel Craig confirmed as 006th screen Bond". London: Guardian Unlimited. 14 October 2005. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2005/oct/14/film.filmnews. Retrieved 15 May 2007.

- ^ "Anti-Bond protests". Moono. http://www.moono.com/news/news01533.html. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ La Monica, Paul R. (6 November 2006). "Blond, James Blond". CNN (CNN). http://money.cnn.com/2006/11/08/commentary/mediabiz/index.htm. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ "The Name's Bland.. James Bland". Daily Mirror. 15 October 2005. http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/tm_objectid=16251427&method=full&siteid=115875&headline=the-name-s-bland---james-bland-name_page.html. Retrieved 27 December 2006.

- ^ "Casino Royale". Chicago Sun-Times. http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070816/REVIEWS/708160301/1023. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- ^ "New Bond film title is confirmed". BBC. 24 January 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/7206997.stm. Retrieved 24 January 2008.

- ^ "Campbell and Broccoli explain the shift from Brosnan to Craig, hints for Bond 22 plotlines". MI6 News. 18 November 2006. http://www.mi6-hq.com/news/index.php?itemid=4418.

- ^ Archie Thomas (1 November 2008). "'Solace' makes quantum leap in UK.". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117995122.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Bond film smashes weekend records". BBC News. 3 November 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/7705631.stm. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ Dave McNary (2 November 2008). "James Bond finds overseas 'Solace'". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117995151.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 3 November 2008.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office Results from 11/14 - 11/16". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/weekend/chart/?view=&yr=2008&wknd=46&p=.htm. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "James Bond Movies". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/franchises/chart/?id=jamesbond.htm. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ Joshua Rich (16 November 2008). "'Quantum of Solace' Stirs up a Win". Entertainment Weekly. http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,20240780,00.html. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ Claudia Eller (17 November 2008). "Sony braces for life without Bond". Los Angeles Times. http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/entertainmentnewsbuzz/2008/11/the-enormous-fi.html. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ "Sony Seals Deal For 007". MI6-HQ.com. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/bond_23_sony_distribution.php3. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ^ "Bond 23 Release Dates Confirmed". MI6-HQ.com. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/bond_23_report_jun11.php3. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Thompson, Paul (7 October 2011). "007 now has a name! The new troubled James Bond film will be called Skyfall". The Daily Mail (London). http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-2046172/James-Bond-23-title-revealed-Skyfall.html. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ McNary, Dave (11 January 2011). "Bond to return with Daniel Craig, Sam Mendes". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1118030077. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ "New James Bond film starring Daniel Craig is announced". BBC. 11 January 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-12168421. Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ Tran, Mark (12 January 2011). "Bond 23 confirmed: Daniel Craig back as 007 in new film". Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2011/jan/12/bond-23-daniel-craig-mgm. Retrieved 13 January 2011.

- ^ "Roger Deakins confirms James Bond 23 involvement". MI6-HQ.com. 1 May 2011. http://www.mi6-hq.com/news/index.php?itemid=9414&t=mi6&s=news. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "Judi Dench lets slip top secret date of the next James Bond". MI6-HQ.com. 27 March 2011. http://express.co.uk/posts/view/236984/Judi-Dench-lets-slip-top-secret-date-of-the-next-James-Bond. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ Finke, Nikki, and Mike Fleming (30 January 2011). "Javier Bardem Offered Big Bond #23 Role; MGM Leveraging 007 Distribution With Co-Financing Deal To Improve Its Cash Flow: Jockeying Studios "Increasingly Frustrated"". Deadline.com. http://www.deadline.com/2011/01/javier-bardem-offered-big-bond-role-as-mgm-leveraging-007-distribution-with-co-financing-deal-to-improve-its-cash-flow-jockeying-studios-increasingly-frustrated/. Retrieved 10 February 2011.. WebCitation archive.

- ^ http://abcnews.go.com/Nightline/video/javier-bardem-cause-sahara-human-rights-hollywood-14694971

- ^ "Ralph Fiennes is linked to Bond 23 role, shooting in December". MI6-HQ.com. 26 March 2011. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/bond_23_report_mar11.php3. Retrieved 30 March 2011.

- ^ http://www.totalfilm.com/news/albert-finney-joins-bond-23

- ^ "James Bond 23 to be called 'Skyfall'". The Daily Telegraph (London). 3 November 2011. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/jamesbond/8866666/James-Bond-23-to-be-called-Skyfall.html.

- ^ "Ben Whishaw cast as Q in new James Bond film Skyfall". BBC News. 25 November 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-15889689.

- ^ "Bond 23 Location Scouting In South Africa". MI6-HQ.com. 6 April 2011. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/bond_23_report_apr11.php3. Retrieved 6 April 2011.

- ^ "Bond will be shot in India". Hindustan Times. 30 July 2011. http://www.hindustantimes.com/Bond-will-be-shot-in-India/Article1-727452.aspx. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Latest James Bond film to be shot in India". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Latest-James-Bond-film-to-be-shot-in-India/articleshow/9802594.cms. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Bond going off track in India?". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hollywood/news-interviews/Bond-going-off-track-in-India/articleshow/9693257.cms. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ MI6-HQ Copyright 2011 (31 August 2011). "Information and Broadcasting Ministry of India green-lights Bond 23 to shoot in the country :: Bond 23 (2012) - The 23rd James Bond 007 Film :: MI6". Mi6-hq.com. http://www.mi6-hq.com/sections/articles/bond_23_report_aug11d.php3?s=bond23&id=02939. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "Bond could have shot". Timesofindia.indiatimes.com. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/entertainment/hollywood/news-interviews/Bond-could-have-shot/articleshow/10115343.cms. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ "007 James Bond to return to Turkey". Medasist International. 2 September 2011. http://newsfromturkey.net/007-james-bond-to-return-to-turkey. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "Scotland's oldest inhabited castle to star in next James Bond movie". The Daily Record. 25 September 2011. http://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/scottish-news/2011/10/07/goldenaye-scotland-s-oldest-inhabited-castle-to-star-in-next-james-bond-movie-86908-23472704/. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ http://www.purepeople.com/article/james-bond-premieres-informations-officielles-sur-skyfall_a90482/1

- ^ Gantz, Jeffrey (17 November 2006). "Casino Royale". The Boston Phoenix. http://thephoenix.com/boston/Movies/27760-Casino-Royale-I/?rel=inf. Retrieved 15 September 2009.

- ^ von Dassanowsky, Robert (2000). International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers. http://www.filmreference.com/Films-Ca-Chr/Casino-Royale.html.

- ^ Both Allen and Peter Sellers are listed as uncredited writers of Casino Royale on the Internet Movie Database. Allen's work on the script is discussed in Baxter, John (2000). Woody Allen: A Biography. Carroll & Graf. pp. 114–137. See also Pitts, Michael R. (2010). Columbia Pictures Horror, Science Fiction and Fantasy Films, 1928-1982. McFarland. p. 32.

- ^ The similarity between Allen's character in Royale and Allen's earlier character in Pussycat has been noted in Wernblad, Annette (1992). Brooklyn is not expanding: Woody Allen's comic universe. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. p. 26.

- ^ "Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. announces acquisition of Never Say Never Again James Bond assets" (Press release). MGM. 4 December 1997. Archived from the original on 5 May 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080505213137/http://mgm.mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&item=47&printable. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ Sterngold, James (30 March 1999). "Sony Pictures, in an accord with MGM, drops its plan to produce new James Bond films.". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1999/03/30/business/media-business-advertising-sony-pictures-accord-with-mgm-drops-its-plan-produce.html?n=Top%2fNews%2fBusiness%2fSmall%20Business%2fMarketing%20and%20Advertising. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- ^ "Academy Awards Database". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. http://awardsdatabase.oscars.org. Retrieved 3 November 2007.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (5 December 2008). "Ask Mick LaSalle". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/12/05/PK6114C535.DTL&type=movies. Retrieved 6 December 2008.

- ^ "Top 25 Movie Franchises of All Time: #2". IGN. http://movies.ign.com/articles/752/752240p1.html. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- ^ "Dr. No". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/dr_no/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Dr. No (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/dr_no/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "From Russia with Love". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/from_russia_with_love/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "From Russia with Love (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/from_russia_with_love/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Goldfinger". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/goldfinger/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Goldfinger (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/goldfinger/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Thunderball". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/thunderball/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Thunderball (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/thunderball/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "You Only Live Twice". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/you_only_live_twice/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "You Only Live Twice (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/you_only_live_twice/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "On Her Majesty's Secret Service". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/on_her_majestys_secret_service/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "On Her Majesty's Secret Service (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/on_her_majestys_secret_service/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Diamonds Are Forever". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/diamonds_are_forever/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Diamonds Are Forever (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/diamonds_are_forever/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Live and Let Die". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/live_and_let_die/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "Live and Let Die (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/live_and_let_die/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Man with the Golden Gun". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/man_with_the_golden_gun/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Man with the Golden Gun (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/man_with_the_golden_gun/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Spy Who Loved Me". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/spy_who_loved_me/. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- ^ "The Spy Who Loved Me (Top Critics)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/spy_who_loved_me/#top-critics-numbers. Retrieved 1 September 2011.